“No case interested and perplexed me so much as the brightly colored hinder ends and adjoining parts of certain monkeys.”

— Charles Darwin

It seems that our male ancestors weren’t fighting much over dates for the past few million years (until agriculture pitted them against each other), but that doesn’t mean Darwin was wrong about male sexual competition being of crucial importance in human evolution. Even among bonobos, who experience little to no overt conflict over sex, Darwinian selection takes place, but on a level Darwin himself probably never considered — or dared discuss publicly, anyway. Rather than male bonobos competing to see who gets lucky, they all get lucky, and then let their spermatozoa fight it out.

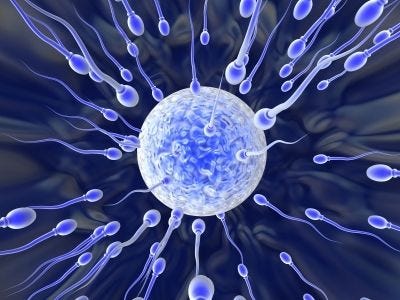

The idea is simple. If the sperm of more than one male are present in the reproductive tract of an ovulating female, the spermatozoa themselves compete to fertilize the ovum. Females of species that engage in sperm competition typically have various tricks to advertise their fertility, thereby inviting more competitors. Their provocations range from sexy vocalizations or scents to genital swellings that turn every shade of lipstick red from Berry Sexy to Rouge Soleil.

The process is something of a lottery, where the male with the most tickets has the best shot at winning (hence, the chimp and bonobo’s huge sperm-production capabilities). It’s also an obstacle course, with the female’s body providing various types of hoops to jump through and moats to swim across to reach the egg — thus eliminating unworthy sperm.

Although Darwin might have been “perplexed” by it, sperm competition serves the central purpose of male competition in his theory of sexual selection, with the reward to the victor being fertilization of the ovum. But the struggle occurs on the cellular level, among the sperm cells, with the female’s reproductive tract being the field of battle. Male apes living in multi-male social groups (such as chimps, bonobos, and humans) have larger testes, housed in an external scrotum, mature later than females, and produce larger volumes of ejaculate containing greater concentrations of sperm cells than apes in which females normally mate with only one male per cycle (such as gorillas, gibbons, and orangutans).

And, who knows? Perhaps Darwin would have recognized this process, if he’d been a bit less indoctrinated by Victorian notions of female sexuality. Anthropologist and primatologist Sarah Hrdy contends that “it was Darwin’s presumption that females hold themselves in reserve for the best available male that left him so puzzled by sexual swellings.” Hrdy doesn’t buy Darwin’s “coy female” schtick for a minute: “Although appropriate for many animals, the appellation ‘coy’ — which was to remain unchallenged dogma for the succeeding hundred years — did not then, and does not today, apply to the observed behavior of monkey and ape females at mid-cycle.”

It’s possible Darwin was being a bit coy himself in his writings on the sexuality of human females. The poor guy had already insulted God, as most people — including his loving, pious wife—understood the concept. Even if he suspected something like sperm competition had played a role in human evolution, Darwin could hardly be expected to drag the angelic Victorian woman down from her pedestal. Bad enough that Darwinian theory depicts women evolving to prostitute themselves for meat, access to male wealth, and the rest of it. To have argued that ancestral females were shameless trollops motivated by erotic pleasure would have been too much.

Still, with characteristic awareness of just how much he didn’t — and couldn’t — know, Darwin acknowledged, “As these parts are more brightly coloured in one sex [female] than in the other, and as they become more brilliant during the season of love, I concluded that the colours had been gained as a sexual attraction. I was well aware that I thus laid myself open to ridicule. . . .”

Perhaps Darwin did understand that the bright sexual swellings of some female primates served to stoke male libido, which shouldn’t be necessary according his sexual selection theory. There is even evidence that Darwin may have had reason to ponder sperm competition in humans. In a letter from Bhutan, where he was gathering plants, Darwin’s old friend Joseph Hooker discussed the polyandrous humans he was encountering, where “a wife may have 10 husbands by law.”

I do not know why bonobos have been ignored by most anthropologistS for so many decades.

Another great article! And really well-written.

Since you brought up prehistoric origins, what do you think about my "theory" which I've written about in books and articles—

“Unlike other primate females who show visible signs of fertility that signal to males their readiness for reproduction, women’s hidden ovulation meant that reproduction was hit-or-miss. To compensate for this threat to survival and to negotiate the who, how, where, and when of humanity’s new all-the-time, anytime “mating game,” humans had to evolve more complex forms of communication. Was it possible that our unique hyper-sexuality, uncoupled from instinctual reproduction, drove the evolution of speech and language that ultimately developed into human civilization?”