Not all of his contemporaries agreed with Darwin’s views on human sexual nature. In fact, one of the pioneers of American anthropology, much admired by Darwin, came to very different conclusions about how our ancestors conducted themselves.

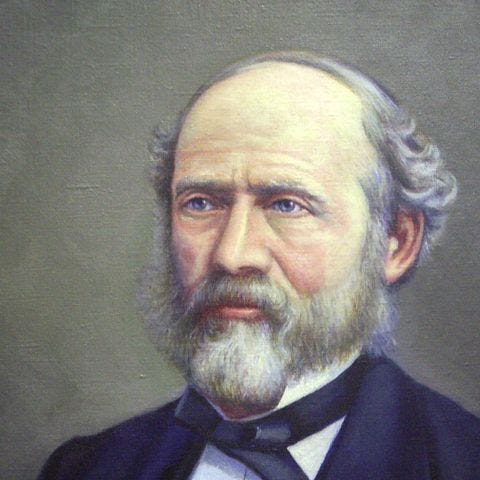

To white people, he was known as Lewis Henry Morgan (1818–1881), a railroad lawyer with a fascination for scholarship and the ways in which societies organize themselves. The Seneca tribe of the Iroquois Nation adopted Morgan as an adult, giving him the name Tayadaowuh-kuh, which means “bridging the gap.” At his home near Rochester, New York, Morgan spent his evenings studying and writing, trying to bring scientific rigor to understanding the intimate lives of people made distant by time or space. The only American scholar to have been cited by each of the other three intellectual giants of his century, Darwin, Freud, and Marx, many consider Morgan the most influential social scientist of his era and the father of American anthropology.

“There seems to be no escape” from the conclusion that a “state of promiscuous intercourse” was typical of prehistoric times, “although questioned by so eminent a writer as Mr. Darwin.”

Ironically, it may be Marx and Engels’s admiration that explains why Morgan’s work isn’t better known today. Though he was no Marxist, Morgan doubted important Darwinian assumptions concerning the centrality of sexual competition in the human past. This stance was enough to offend some of Darwin’s defenders — though not Darwin himself, who respected and admired Morgan as a friend. In fact, Morgan and his wife spent an evening with the Darwins during a trip to England. Years later, two of Darwin’s sons stayed with the Morgans at their home in upstate New York.

Morgan was especially interested in the evolution of family structure and overall social organization. Contradicting Darwinian theory, he hypothesized a far more promiscuous sexuality as having been typical of prehistoric times. “The husbands lived in polygyny [i.e., more than one wife], and the wives in polyandry [i.e., more than one husband], which are seen to be as ancient as human society. Such a family was neither unnatural nor remarkable,” he wrote. “It would be difficult to show any other possible beginning of the family in the primitive period.” A few pages later Morgan concludes that “there seems to be no escape” from the conclusion that a “state of promiscuous intercourse” was typical of prehistoric times, “although questioned by so eminent a writer as Mr. Darwin.”

Morgan’s argument that prehistoric societies practiced group marriage (also known as the primal horde or omnigamy—the latter term apparently coined by French author Charles Fourier) so influenced Darwin’s thinking that he admitted, “It seems certain that the habit of marriage has been gradually developed, and that almost promiscuous intercourse was once extremely common throughout the world.”

With his characteristic courteous humility, Darwin agreed that there were “present day tribes” where “all the men and women in the tribe are husbands and wives to each other.” In deference to Morgan’s scholarship, Darwin continued, “Those who have most closely studied the subject, and whose judgment is worth much more than mine, believe that communal marriage was the original and universal form throughout the world. . . . The indirect evidence in favour of this belief is extremely strong. . . .”

Please remember that when Morgan described the sexual practices of various societies around the world as “promiscuous,” he wasn’t being judgmental; he was describing behavior that was normal to the people in question. In the common usage, promiscuity suggests immoral or amoral behavior, uncaring and unfeeling. He was simply calling attention to the non-exclusivity of these relationships, not implying any absence of intimacy or respect. In fact, given that groups of foragers (either those still existing today or in prehistoric times) rarely number much over 100 to 150 people, each adult is likely to know every one of his or her partners deeply and intimately—probably to a much greater degree than a modern man or woman knows his or her casual lovers.

Morgan made this point directly in Ancient Society, writing, “This picture of savage life need not revolt the mind, because to them it was a form of the marriage relation, and therefore devoid of impropriety.”

So, if promiscuity suggests a number of ongoing, nonexclusive sexual relationships, then yes, our ancestors were likely far more promiscuous than all but the randiest among us. On the other hand, if we understand promiscuity to refer to a lack of discrimination in choosing partners or having sex with random strangers, then our ancestors were likely far less promiscuous than many modern humans. Given the contours of prehistoric life in small bands, it’s unlikely that many of these partners would have been strangers.

I knew there was a reason I always liked the \seneca. The first shaman I got to know was a Seneca.

Chris, I love your questioning of our sexual myths.

I’ve done a bit of that myself in my books and articles, especially my recent “Questioning Sex” series.

My most recent article in the series—“Questioning Sex #8: Is Sex a Public Health Crisis?” asks the question: Has humanity been polluted by millennia of toxic sexual shame? What are the consequences of this collective trauma?

https://medium.com/@jerryiweinstock/questioning-sex-8-is-sex-a-public-health-crisis-aa4f28930e60

“When you think of a natural resource that’s been polluted by human activity, you think of the water we drink, the air we breathe, and the earth that grows the food we eat. You don’t think of sex. But maybe you should!

“Like lead in our drinking water, asbestos in our homes, and toxic chemicals and plastic in our food, our inheritance of sexual shame pollutes us as individuals and makes society sick.”